Invest Passively: Because Stock Picking Is a Matter of Luck

At True Wealth, we put a lot of care into building your portfolio. But we don't put any energy into selecting individual stocks. Why is that?

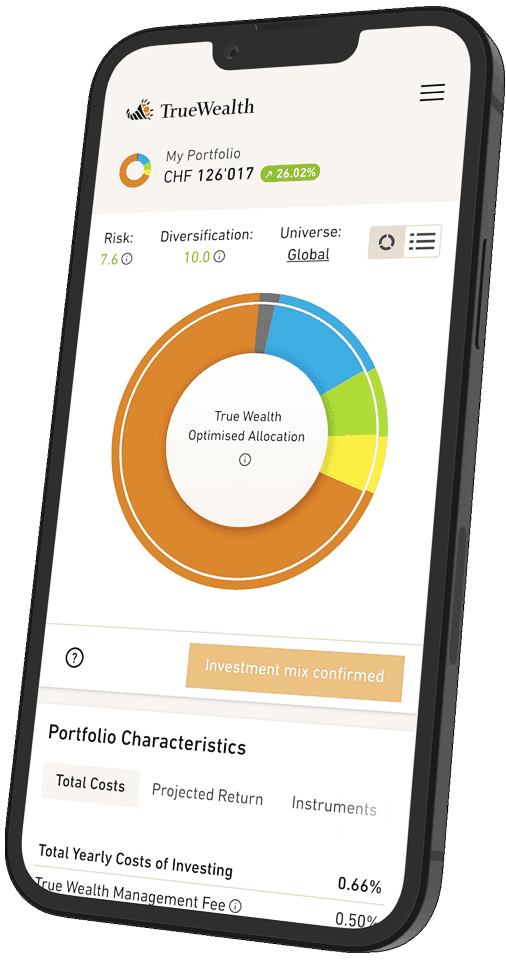

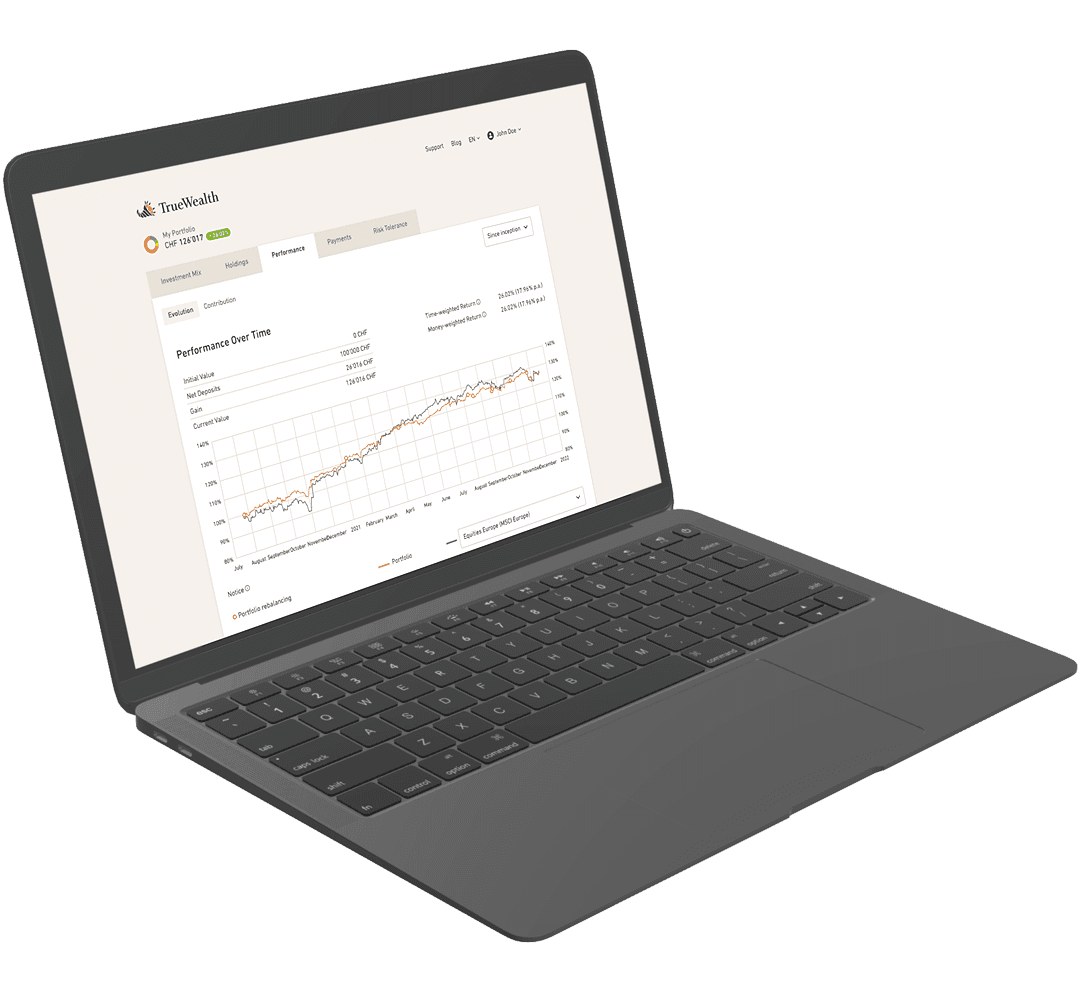

At True Wealth, we pursue a passive investment approach for our clients. To many ears, this sounds strange at first: What do you mean by passive? Don't they do anything? Far from it. We take great care to ensure that our investors get the best possible portfolio. One that suits their personal risk capacity and risk appetite. But the one thing that we deliberately refrain from doing is: We don't put energy into picking individual stocks. And this is the passive aspect of our approach.

There are three good reasons for this:

Most People Pick the Wrong Stocks

Many investors try to pick the right stocks and buy and sell them at the right moment. This usually goes wrong; studies show that most of these investors lose money in the long run. Out of all the studies, the one by Terrance Odean impressed me the most.

For this study, the researchers examined all trades in more than 10'000 trading accounts of a broker over seven years. In this way, they gained insights into every transaction made by these clients – almost 163'000 trades in total. They then grouped each of the trades, which followed each other closely in time, into pairs: Whenever an investor sold one share and immediately bought another, this would count as a trade.

The researchers' thesis: If an investor sells one share and buys another instead, then he has a clear opinion about these two shares. He exchanges one share for another. So he believes that his new acquisition will perform better than the old share from the portfolio. But is this belief well-founded?

Barber and Odean have now compared the performance of the swap pairs over a period of one year. The result is shocking: On average, the newly bought shares performed worse than the ones just sold. And considerably worse, by as much as 3.2 percent (And this doesn't even include the fact that each of the investors had to pay trading fees for the bad swap in the portfolio).

For the 10'000 private investors, this does not necessarily mean that they lost money. In a good stock market year, they may still have made a profit. But they invested below their potential – and below the potential of the market. But who made the money they left on the table? The professionals?

Professionals Can Hardly Do Better Than Amateurs

Private investors sell the wrong shares, and they buy the wrong shares. This may be partly because they are influenced by the news. They can be influenced by all of the information that flies around their ears in a disorderly manner on a daily basis.

Professionals are more selective. They also process a lot of information. However, they react less impulsively to what reaches their ears ad hoc, and they search instead for information in a targeted way. They usually have good training and some have years of experience, which helps them to classify the information against a meaningful background. And – because they are paid for it – they also have the time to look for information that has not yet made it into the headlines.

That's why they like to call themselves the «smart money». One would think that with this background they should be able to solve the task of skimming off for themselves and their clients the extra returns that private investors have missed out on.

However, the results of over fifty years of research show a very different picture. Typically, every year two out of three mutual funds underperform the benchmark they are trying to beat, as John C. Bogle summarises. So is it necessary to find the one manager who has beaten the market and two of their peers?

Fund Managers Are Also Just Lucky

Daniel Kahneman was able to take a look at the world of professionals from the inside. The psychologist, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2002, was able to work with the internal data of an asset manager on Wall Street. The firm meticulously recorded the performance of its managers. After all, it is not least the performance of the assets under management that decides at the end of the year how high the bonus will be for each of the managers.

What interested Kahneman the most from this internal data was: Are the portfolio managers who did well this year also the best next year? Is good performance consistent? To do this, he examined eight years of results and compared all the years in pairs with each other: Year one with year two, year one with year three – all the way to year seven with year eight. This resulted in 28 correlation coefficients, exactly one for each pair of years in the comparison.

Kahneman, of course, only started this calculation in the first place because he suspected that performance would not be particularly consistent, and that ultimately each manager's annual performance would depend on luck. Nevertheless, he suspected that performance would also depend a little on skill. Just like in a poker game. There, the cards are always a matter of luck, but good players bet more on good hands and less when they get bad cards.

The result surprised even the sceptic Kahneman: It was even weaker than expected. The average of the correlations was 0.01 – professional stock picking was no better than a game of dice (There, the correlation between the dice rolls would be 0.00 – if you roll long enough).

Do You Want to Pay Professionals for Luck?

We are used to paying for performance. We actually even like to pay for good performance. But do we really want to pay for luck? That's why for us at True Wealth the approach is clear: We save ourselves the costs of stock picking and compose your portfolio exclusively from low-cost exchange traded funds (ETFs) that do without the need for such selection.

Links

- Terrance Odean: Do Investors Trade Too Much?

- Brad M. Barber and Terrance Odean: Trading Is Hazardous to Your Wealth – The Common Stock Investment Performance of Individual Investors.

- John C. Bogle: Common Sense on Mutual Funds – New Imperatives for the Intelligent Investor (New York: Wiley, 2000)

- Daniel Kahneman: Thinking, Fast and Slow. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011)

About the author

Oliver is one of the founders of Switzerland's largest online shops: the online retailer Galaxus and the electronics specialist Digitec. Together with Felix, he launched True Wealth AG in 2013.

Ready to invest?

Open accountNot sure how to start? Open a test account and upgrade to a full account later.

Open test account