Talk – Start-up country Switzerland with Nicola Forster

Switzerland is an innovative country with world-leading science centers that produce successful spin-offs, but what exactly is the situation for founders in Switzerland today?

Welcome to the second episode of our podcast series on the topic of «Start-up Switzerland». In this exciting series, we shed light on the many facets of the Swiss start-up scene and talk to influential personalities. Our second guest is a founder in the political and social sense: Nicola Forster.

Nicola, you have chaired the Green Liberal Party in Zurich and the Swiss Society for the Common Good (SSCG). You also founded the two think tanks «foraus» and «staatslabor». Speaking of founding Switzerland: the mythical place where Switzerland was founded is known as the Rütli. There is a story about what happened there over 160 years ago in connection with the SSCG. Can you tell us more about this story?

Yes, the funny thing is that the Rütli was described by Schiller, although he himself was never on the Rütli. Schiller was never in Switzerland, he only heard how beautiful it is there. Goethe, on the other hand, actually traveled through Switzerland and wanted to write William Tell, but then had no time and left the material to Schiller, and that's how our national myth came into being.

The SSCG, the Swiss Society for the Common Good, which I presided over, was founded in 1810, even before modern Switzerland. 160 years ago, the SSCG went on an excursion and passed by the Rütli. They saw that there was a construction trailer on the Rütli and asked what it was and what was happening there. They were told that the Rütli was to be built over with a hotel. They said: «As good patriots, we have to save it!». Then they organized a national fundraising campaign. Today we would call it crowdfunding. With the help of the young people and children who collected money all over Switzerland, especially in the cities, to save the Rütli, they were able to buy the Rütli and prevent the hotel from being built.

A year later, it was decided to donate the Rütli to Switzerland, the Swiss Confederation, and in return to take over its administration, which has remained the case to this day. This is why, for example, the 1st August celebrations on the Rütli are organized by the SSCG. This has been in the media again and again in recent months, because the National Council, among others, was of the opinion that the SSCG should take back the administration. As you can see, the Rütli is a very controversial, symbolically charged place. But it is of course exciting to be in such a role.

Switzerland was already in a state of tension 160 years ago, and I believe that the purpose of buying the Rütli meadow was actually a gesture to help patch up the conflict between conservatives and liberals.

Exactly, a symbol was needed at the time. Modern Switzerland was founded in 1848, which was an important date for the liberals and later also for the left. Of course, the myth of 1291 is also very important for the conservatives and also for the cantons that lost in the Sonderbund War. At the time, people were looking for unifying elements to celebrate something of the losers.

That is why the Rütli is so important, because it is a symbol of the old Switzerland. That's why we celebrate August 1 and not September 12, 1848. We celebrate the old mythical Switzerland in order to build a bridge to the losing cantons of the time, who lost in the Sonderbund War. I think it was a very clever decision not to simply use the symbolism of the modern new, but to try to bring the losers on board.

Back to the topic of «founding»: You didn't found companies in the economic sense, but in the political sense, namely the aforementioned think tanks «staatslabor» and «foraus». What motivated you to do this?

I studied law and had actually signed up with a law firm to work as a lawyer in the international field. I have always been fascinated by international matters. In the last few months of my studies, I was allowed to lead a political campaign for the free movement of persons. It was about the extension to Bulgaria and Romania, there was a vote and I was allowed to lead the youth campaign throughout Switzerland for all the parties that were in favor. One was not in favor, I won't say which one. That's when I realized that I have a talent for bringing people together and developing a political story that works for young people in particular.

The «Erasmus» generation, the «Easyjet» generation, as it was negatively referred to, also has an attitude to life and the expectation of being able to continue living in a networked world. This requires a political offer and I realized that this fascinates me. I have a bit of a talent for it and want to get involved. At the same time, I saw that I could now become a lawyer, something completely different. At the time, I felt that my heart beats for entrepreneurship, for creating, for doing. That's why I didn't pursue the other career path in the end, but instead focused fully on entrepreneurship and took out a loan of 10,000 francs from my parents to somehow bridge the first year.

Soon afterwards, we were able to hire our first person, a managing director and so on. Once you're in start-up mode, it's extremely difficult to get out again. Then you always end up in the next thing. Operation Libero was basically the first spin-off from foraus, the think tank we had previously founded. The «staatslabor» was then founded at a later date when I realized that there was a great need for innovation in administration and government.

Founding gives you adrenaline, you realize that you can really build something with your energy, and then it's very hard to imagine going back to the other world, although I've never really been in the other world.

Would you start a company again?

Yes, absolutely. I think starting something when you're 25 is a huge experience. You also have to be prepared to sacrifice a lot, especially financially. If I had become a lawyer in a commercial law firm, my financial situation would obviously be different today, but that wasn't my main focus.

What does it take for a successful start-up? Would you recommend it to anyone and everyone?

I have the feeling that we actually already have a chance in Switzerland. In contrast to many other countries, we have a social safety net. We are doing well. Many of us have a starting position in that we don't have to starve financially, that we often have a good education, that we have a safety net somewhere. So even if you don't have much money, you can still take the plunge.

Even if it doesn't work out, you don't immediately have existential problems. That's why I think it would be desirable if more people started their own business. It's almost a bit surprising that so few people back start-ups. Maybe it's because we're doing well. It's a kind of honey pot that we find ourselves in.

The subject of failure is a difficult one. People don't like to talk about it. Is there anything you would say that didn't work out? Maybe you learned something from it?

Yes, all the time. I think as a founder you naturally try to succeed more than you fail. But failure is also part of it. If the failure rate is 49%, then you're on the right track. Failure is also celebrated a bit these days. But I still believe that it doesn't go down well in Swiss society when you see that someone has fallen flat on their face.

It's very different to the USA, for example. In Silicon Valley, it's quite normal to have done ten things, seven of which failed. But three have gone relatively well and one is great. If you talk to founders from the USA, even if they have only started something and it has failed, they tell you about it.

What is different in Switzerland? Are we perfectionists?

Yes, maybe that too. We are perfectionists. You also have a general desire for security, which is expressed in our institutions, in our social system. You see people all around you who live in this security. Then to realize: «I'm the one who fails and my peers have all made it.» Of course that's not nice, is it?

On the other hand, when you're in Silicon Valley, you realize: Everyone else fails all the time too. But there are also a few who do really great things. I once lived in New York for two years and always found it very impressive, this spirit of getting up again and doing the next thing. But you also have to say that perhaps the topic of mental health problems, which is fortunately becoming more and more of an issue now, is also very relevant. I think you can almost only live such a lifestyle if you're healthy. If you can really push yourself to the limit. I think that's a bit of the downside of the model in the USA. If you crash there, you really crash and it hurts. Here, the upward spikes are not as strong, but neither are the downward ones. That's the beauty of our system.

But back to the subject of failure. I think we always had relatively existential issues in these organizations, where we didn't know whether we would still be able to finance our salaries in three months' time. For me, taking risks was never a problem. I always went all-in. I think if it's just you, you can take it. But from the moment you start paying salaries, where there are dependencies, it gets more complicated.

In my first organizations, everyone was 25 years old. At that age, it's not so dramatic when a job ends and you have to look for something else. But when you're dealing with 40-, 50-, 60-year-olds, where issues like family, retirement and so on are involved, then it's more difficult. Then you're more likely to have sleepless nights when you realize that it might be over in six months. That's not just nice.

Where do you see the economic benefits of entrepreneurship?

I think the benefits are huge. If you look back in history: Switzerland was a relatively poor country. During industrialization, it managed to position itself as an innovative country. That was actually the start of its rise. Back then, it wasn't just about large companies, which was often the case later on. We owe a great deal to individual personalities like Alfred Escher. What Escher achieved is incredible when you look back today. What he did for the Gotthard Tunnel, for the ETH, for CS, well, that's a bad example at the moment, but what a single person was able to achieve is incredible.

Also what a foundation Switzerland is. Modern Switzerland came into being because 50 people got together for a few weeks, and that was after a civil war - we must never forget that. The Sonderbund War of 1847 was a civil war in Switzerland. To sit down together a few years later and say: «Now we are founding a modern country». That is mega impressive. I think the security we have today has sometimes caused this spirit, which is what makes Switzerland so special, to suffer a little. You also get the feeling, okay, why should we try so hard?

How do you rate the framework conditions for start-ups?

Not bad, I really don't think we're in a bad position. There are those who are still complaining. I have the impression that the quality of life is high. It's relatively easy to recruit people to work here in Zurich, in Switzerland. You have high personnel costs. But you have good people who come to work here. You have universities that are among the best internationally. More and more people are coming onto the market that you can recruit directly for your organizations. That's fantastic.

I think the tax system is also competitive. I feel like we have a bit of a problem in the venture capital area. The first phase is relatively easy to finance, up to maybe 10 million. First «friends and family», then the first venture capitalists (VCs) come into play. But then, when it gets to the larger figures, it becomes more difficult. Then you quickly find yourself in Berlin, the USA, Israel or London.

Thank you very much for the interview, Nicola.

About the author

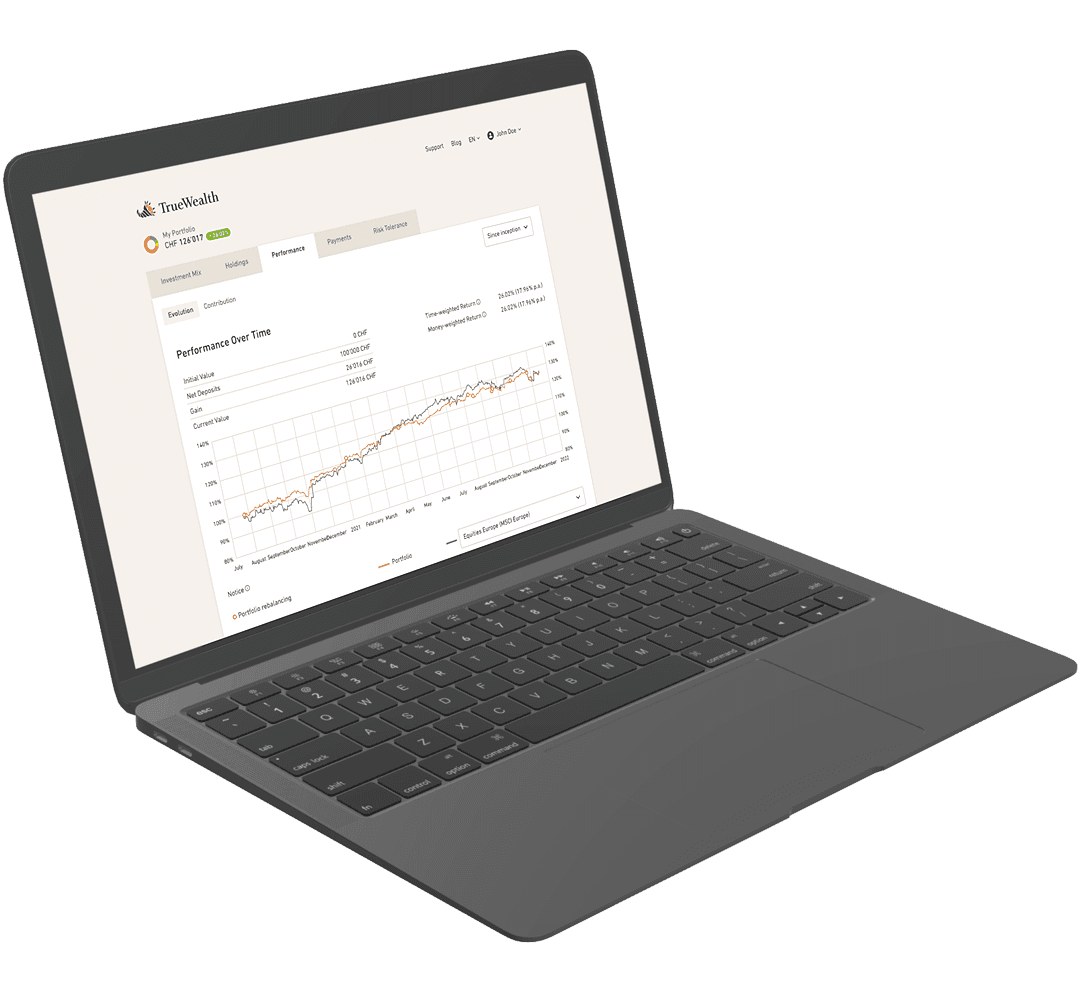

Founder and CEO of True Wealth. After graduating from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) as a physicist, Felix first spent several years in Swiss industry and then four years with a major reinsurance company in portfolio management and risk modeling.

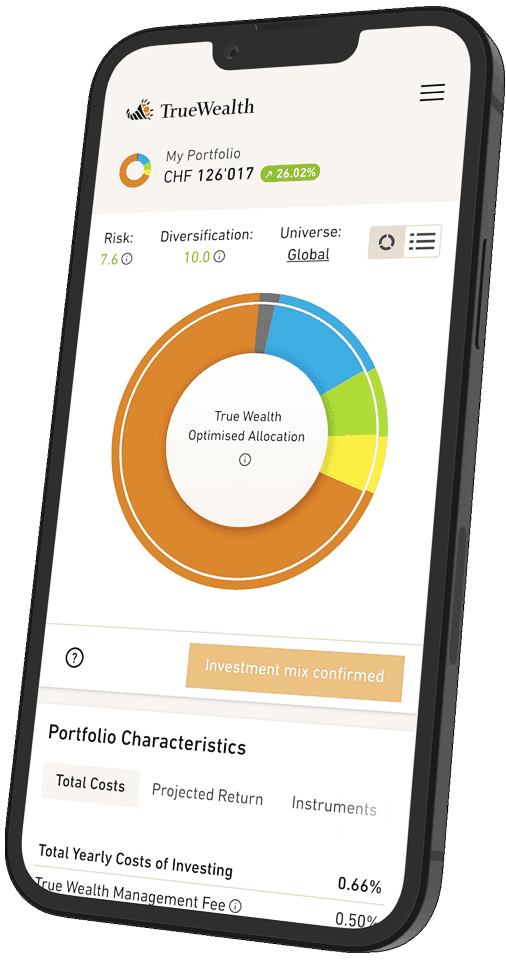

Ready to invest?

Open accountNot sure how to start? Open a test account and upgrade to a full account later.

Open test account