Talk – Capitalism and the Market Economy

What is capitalism? What is wrong with capitalism? And how can we fix it? In their book, Jürg Müller and his co-author vividly show how governments have repeatedly been forced to rescue banks in order to stabilize capitalism, and how these interventions are becoming increasingly drastic in the digital age.

The source of the problem is systemic risks that benefit a few but whose costs are borne by the general public. This destroys trust in market economy principles and ultimately the foundations for a free, open and democratic society.

Jürg Müller, economist and Director of Avenir Suisse, is one of the few people to make transparent the design flaws in our financial system. His proposed solution in his latest book «Capitalism and the Market Economy» is both revolutionary and irritating.

Table of contents:

02:23 - Difference between capitalism and a market economy?

04:27 - The invention of corporations and its consequences

16:00 - Bank runs: the economic damage of systemic risks

28:03 - The solvency rule as a proposed solution

37:34 - The future of financial services in a digital world

46:14 - A market-based, decentralized model as a solution

58:18 - The political feasibility

The motivation behind the book «Capitalism and the market economy»

Jürg, what was the motivation behind writing this book?

To answer this question, we have to look back at our first book. The motivation for this book was closely linked to the financial crisis of 2008. After the 2008 crisis, my co-author was working in a bank, while I was in academia doing a PhD in this field. We were both unhappy with the way both academia and industry were responding to the crisis.

We met once again in a London pub and, as sometimes happens, an idea came to us there - not necessarily a sober one, but rather a spontaneous one: "Let's write a book". That's how it all began. This motivation was the starting point for our first book - a detailed analysis of what had gone wrong in the financial world. We asked ourselves whether digitalization played a role in this and whether there were ways to make things better. Writing the book was a long process. What began as a spontaneous idea developed into a serious project. The first book was relatively technical and microeconomically oriented. It gave us the opportunity to discuss with experts and was translated into eight languages. However, it did not trigger a broad public debate as it was a visionary look into the future. Based on this feedback, we decided to rethink the topic and ask ourselves how we could turn our vision into reality. So we decided to take a step back, look at the problem on a macroeconomic level and consider how we can achieve our goals.

Definition of capitalism and market economy

We started from the generally prevailing definition of capitalism. This definition focuses on two issues. Firstly, property rights and secondly, markets. That is a conceptual definition of capitalism. However, there is also the understanding of capitalism as an epoch in history. This began with the Industrial Revolution, between the 17th century and the 18th century in England. Today, the entire economic order is like this. If you now place the two definitions, the conceptual and the historical definition, side by side, you can see that they are not congruent. Property rights and markets have existed for centuries, if not millennia. But in the phase we call capitalism today, something else happened. We believe that what happened there is the defining element of capitalism and that a market economy, in the sense of property rights and free exchange, is something different from what happened at that time and still characterizes our economic order today.

The existence of corporations

A fundamental element in understanding capitalism is the existence of corporations. Famous examples are the colonial trading companies such as the East India Company and the Hudson Bay Company, which shaped the legal concept of the corporation. The founding of the Bank of England marked a turning point by combining corporations with the long-established financial practices of banking. This merging of corporations with banking was revolutionary because it enabled the creation of money and credit on an unprecedented scale.

Many people wrongly assume that money is created exclusively by central banks and that they have a monopoly on money creation. However, this is not entirely true. While central banks have a monopoly on banknotes and other forms of physical money, money is also created on the balance sheets of commercial banks, known as book money. Most of the money we use, be it when shopping in the supermarket or paying with a credit card, exists in the form of scriptural money on bank balance sheets. It was the Bank of England that introduced this innovation: the ability to create money not only physically, but also on the balance sheets of corporations.

The trick of double-entry bookkeeping, extending balance sheets and creating money, was already known. But it took the Bank of England to spread this concept throughout the system and apply it to the balance sheets of corporations. Corporations enable the aggregation of capital and provide a flexibility that is crucial for the financing of capital-intensive processes.

The pact between the English king and the Bank of England, which we describe in detail in this book, shows that corporations do not simply arise from private contractual relationships. The sovereign, in this case the king, played a decisive role by giving the companies their own legal personality through a "royal charter", i.e. a royal decree. This concept of limited liability, which still applies today, enabled corporations to raise capital and expand their activities.

The bank run and the digital revolution

The Bank of England made a pact with the King that allowed it to be a corporation rather than a personally liable company. This happened in the context of war financing, as so often in history. A well-known economist and economic historian claims that all the central banks of the 18th century were founded to finance wars. The Bank of England was founded to monetize the King's debts. By selling shares and issuing banknotes, it financed the King's debts. This public-private partnership made it possible to save the economy from the deflation trap and support economic growth.

However, it was not long before the Bank of England's first problem arose. This problem manifested itself in the form of a bank run. A "bank run" describes the phenomenon of many people simultaneously trying to exchange their book balances at the central bank for cash. This can lead to banks becoming illiquid and collapsing, resulting in the realization of systemic risk. Although this systemic risk existed before the emergence of corporations, it has taken on a new dimension with them. The Bank of England's "bank run" manifested itself relatively quickly and led to state intervention. During the crisis, the bank threatened to become illiquid and collapse. The sovereign intervened and allowed the bank to breach contractual provisions (a form of creditor protection), which saved it from liquidation. This type of intervention, which is now known as a "bail out", helped, but created the wrong incentives in the long term. As a bank, you suddenly have an incentive to take more risks because you know that you will be rescued in bad times. After the Bank of England came other banks, and a kind of ecosystem of banks and the Bank of England emerged. Over time, the Bank of England eventually evolved into a central bank that acted as a lender of last resort, providing stability.

Another decisive turning point was the "Great Depression", which saw the transition from gold-backed money to paper money. This gave central banks new opportunities to intervene. If they can create money out of nothing, they will never become illiquid again. The digital revolution since the 1970s has fundamentally changed the financial system once again. The speed and complexity of financial transactions have increased, making it more difficult to stabilize the system. The traditional control of individual bank balance sheets has become less effective as money is created outside the traditional banking system. Digitalization has meant that more and more institutions, including investment banks and insurance companies, have to be rescued when systemic risks arise from financial contracts and the system threatens to collapse in the event of illiquidity. The increasing interconnectedness and complexity of the financial system has highlighted the need for a new approach to stabilize the system.

The problem with boom and bust cycles

The systemic risks that lead to boom and bust cycles create chain reactions that affect the entire economy. Why is this problematic and what economic damage does it cause?

The simple answer is that it distorts the allocation of resources. In booms and downturns, labor, cement or steel are misallocated due to distorted prices. The euro crisis after 2008, in which entire ghost towns were created in some cases, provided a vivid example of this. Although the market is considered efficient, the credit boom showed that the allocation of resources during the upswing was not efficient. Houses and infrastructure were built that were not actually needed. In Spain, for example, the boom led to people dropping out of education to enter the construction industry, even though there was no need for it. This led to a misallocation of human capital. The boom-bust cycle is a waste of human resources and represents an inefficient allocation. In the crisis, some banks collapse, others are bailed out, but unemployment rises. This in turn is a sign of misallocation: labor cannot be used productively. It is a sign of permanently inefficient allocation. It is important to emphasize that it is not the market economy per se that causes the boom-bust cycle, but the current design of capitalism, especially the combination of the corporate form and banking.

Financial services in a digital world

In your book, you present a convincing example of how financial services can be efficiently mapped in a digital world without triggering chain reactions. You describe a company whose balance sheet combines assets and liabilities. Liability items of one company can serve as asset items of another company and vice versa. This mechanism, known as leverage, can lead to a domino effect in which the default of one company has further serious consequences. A prominent example is the CS-UBS debacle. But the example you give in your book also illustrates this very well using the example of peer-to-peer lending. Of course, companies have a need for financing. An SME needs a loan and traditionally the bank comes into play, which has already built up a relationship of trust with the SME and says: "Okay, I've known you for a long time, I'll give you a credit line of, say, 100,000 francs." In a digital world, such transactions are based on a scoring model. The credit risk of a particular loan is assessed, which then determines the interest rate. On the other hand, there are also investors who say: "Hey, I'm giving my own capital because I have to invest it somehow, and I'm investing some of my money here." You can also aggregate this digitally, but then you no longer have the domino effect.

When you say decentralized, everyone always thinks of blockchain. It's an exciting technology. But when we say decentralized, we mean something else. We mean a 'decentralized accounting system'. In today's financial architecture, you have the large balance sheets in the middle, which create systemic risks. Then you have those who save on one side and those who need money on the other, and everything runs via the central balance sheet. If a balance sheet tips there, then we have this domino effect. The digital revolution has changed that. You can connect the balance sheets directly, you no longer need the large balance sheets at the center. This allows the entire architecture to be more stable and market-based.

The systemic solvency rule

There is a system that generates systemic risks and is hedged by the state, which benefits everyone involved, but a market-based system cannot develop in this way. This insight is by no means new and is in line with the long-standing demand of economists who emphasize that controlling systemic risks in this sector is essential. Our solution is to introduce a systemic solvency rule. This rule would ensure that the costs of safety nets are internalized to create a level playing field for both sectors.

It is important to emphasize that this approach is already integrated into a new world of systemic solvency. In today's world, it is not enough to control systemic risk, as a shadow banking sector would immediately emerge. Therefore, it is crucial to introduce the systemic solvency rule first. In our book, we show step by step how this can be achieved.

After the introduction of the systemic solvency rule, the financial system can be divided into two parts. In one part, which creates systemic risks, measures can be taken to better control these risks and internalize the costs. This would ensure that both types of financial system operate at the same level. However, this separation is only intended as a transitional phase.

Internalizing the costs means that those who cause and profit from systemic risks should also pay for the resulting economic damage. This is not a moral question, but a question of system design. Similar to the introduction of a CO2 levy, such a measure would change the entire system and influence the behavior of the players. By setting an appropriate price, it is to be expected that the decentralized and lean model will prevail in the long term.

My co-author and I are convinced that the market-based, decentralized and lean model will prevail over the centralized, cumbersome and risky model. In our book, we outline the reasons for this assumption and aim to establish a market-based financial system.

Market-based, decentralized model as a solution

Compared to the first book, we have taken a step back. In the first book, we focused very strongly on the technical aspects and made a concrete technical proposal. This can be found in the penultimate chapter. The last chapter is about the international dimension. There we discuss the topic of money. We believe that a discussion about money is necessary if we want to eliminate the systemic risks, in particular the practice of creating money from credit. Because then we have to think about how we can continue to pursue monetary policy.

The beauty is that different types of monetary policy would continue to work. Each form has its advantages and disadvantages. We are proposing one option that we think is worth considering because it has never been done before and offers interesting possibilities. We can take different approaches. When we discuss systemic risks and the change in money creation through credit, the question arises: how can we create money as an alternative? We outline various options. One option is a digital central bank money that can also have negative interest rates because it is digital.

Our proposal builds on the concept we developed in the first book. We propose a system of purely digital money in which a certain amount per capita circulates in the economy. This would be an interesting model, but it also has disadvantages. There would be a kind of money injection per capita in a certain period of time, and the money would flow back via a kind of liquidity fee. This concept has often been discussed in economics to prevent too much money being hoarded in the economy. In fact, this is what happened during the period of negative interest rates. The money was hoarded and did not flow back into the economic cycle. To solve this problem, central banks must be given the tools to intervene. The exact amount of money injected and the liquidity fee would then be a matter for the central bank's experts, who would ensure that everything runs optimally.

We are indeed in favour of a public organization of money. Money is a social construct that enables the division of labor. That is why it should be publicly organized. We would never ban private money, but we believe that there are good reasons to organize it publicly.

However, digital money with today's technology has a decisive disadvantage: it harbors data protection risks. This system could work in two tiers, like the current one. Cash is anonymous, digital money with today's technology is not. This could lead to surveillance and control and therefore needs to be addressed carefully.

Another issue is the injection of money, i.e. the distribution of money to the population. If the central bank increases the money supply due to economic growth in order to prevent deflation, it would distribute the additional money supply directly to citizens. This is a change from current practice, where the money supply is distributed indirectly to the population via the money creation profit.

It is important to emphasize that this is not an unconditional basic income. It is merely an equal distribution of the newly created money. This measure has advantages and disadvantages, but would promote transparency and fairness. It would be more difficult to favor certain groups.

Assessment of the political opportunity of this proposal

What we are presenting here is an attempt to get a discussion going. We are saying: 'We still have time to tackle this in a globally coordinated way'. Our aim is to initiate the transformation of the outdated system from the 17th century into a digital, market-oriented system. Our hope is that this idea will be discussed and that people will think about how it can be implemented. Because if we don't do this, we fear that sooner or later we will end up in a crisis in which confidence in money is lost and a currency crisis occurs. This would result in a permanent loss of purchasing power, which would be extremely destructive for a society.

Ultimately, it's not just about money, but about ensuring that we can live in a free world and that everyone is well off. That is crucial. That is the final step. In the end, it's not just about an economic order. The market economy was never purely economic. Adam Smith was a moral philosopher and a central figure of the Enlightenment. His idea that everyone can decide for themselves was revolutionary. The idea that free interaction leads to positive results for society stands in contrast to a social order in which everything is organized from the top down. A functioning market economy is therefore essential for the functioning of our enlightened and democratic society. I am therefore convinced that we urgently need to devote ourselves to this task.

Jürg, thank you very much for the interview.

Would you like to read more about the topic? Click here for the book “Capitalism and the Market Economy”.

About the author

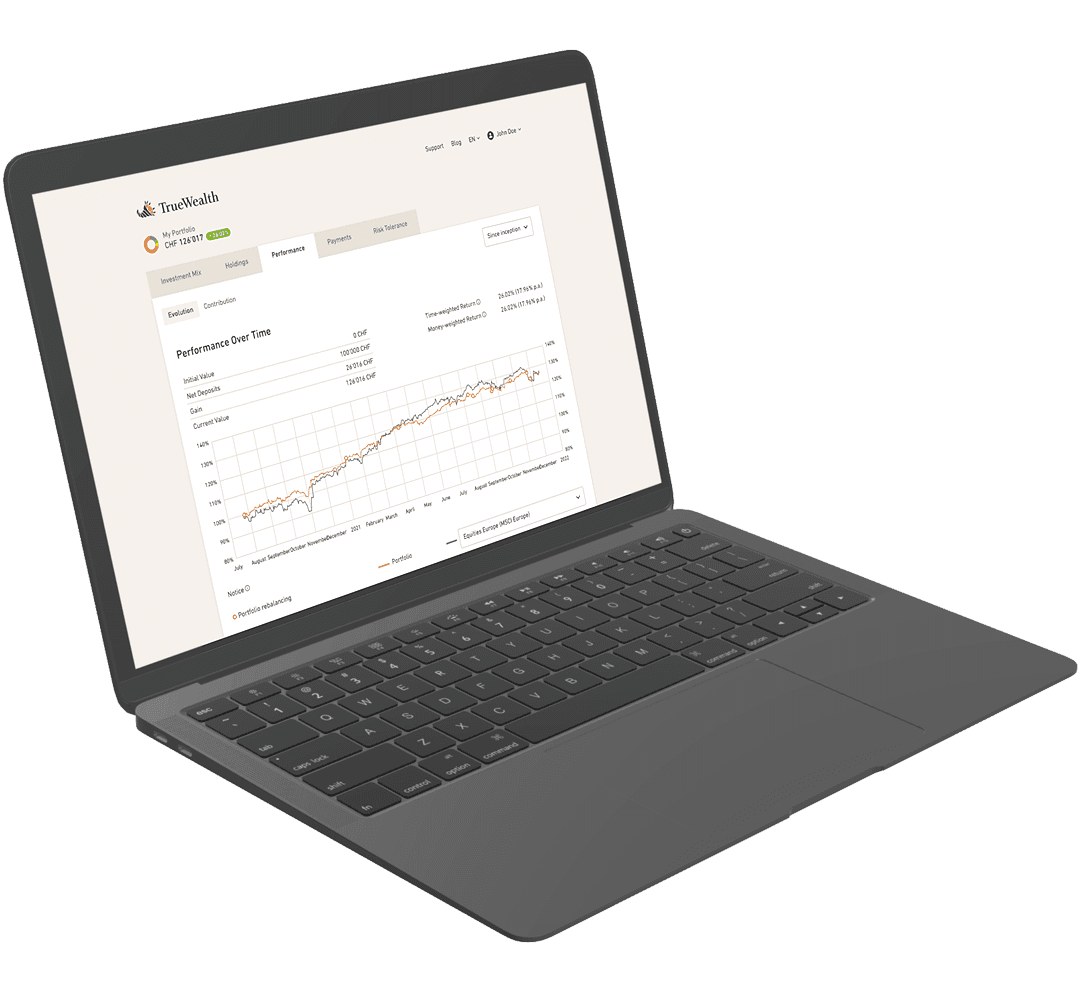

Founder and CEO of True Wealth. After graduating from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) as a physicist, Felix first spent several years in Swiss industry and then four years with a major reinsurance company in portfolio management and risk modeling.

Ready to invest?

Open accountNot sure how to start? Open a test account and upgrade to a full account later.

Open test account